Buchbinder: You’ve said that we have a misguided cultural story about what it means to be human. What does that story tell us?

Shepherd: It tells us that the head should be in charge, because it knows the answers, and the body is little more than a vehicle for transporting the head to its next engagement. It tells us thatdoing is the primary value, while being is secondary. It shapes our perceptions, actions, and experiences of life. It separates us from the sensations of the body and alienates us from the world. And there is no escaping this story; it’s embedded in our language, our architecture, our customs, and our hierarchies. It’s like the ocean, and we are like fish who swim in it and barely notice it because we’ve lived with it since infancy. By interpreting reality for us, stories frame and give meaning to our actions. But there’s a danger to living by a story that you can’t question, because you start to mistake the story for reality. And that’s where my work starts — in formulating questions that can expose that story and hold it to account.

Buchbinder: Where did this story come from?

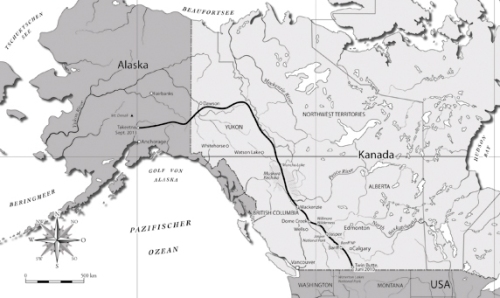

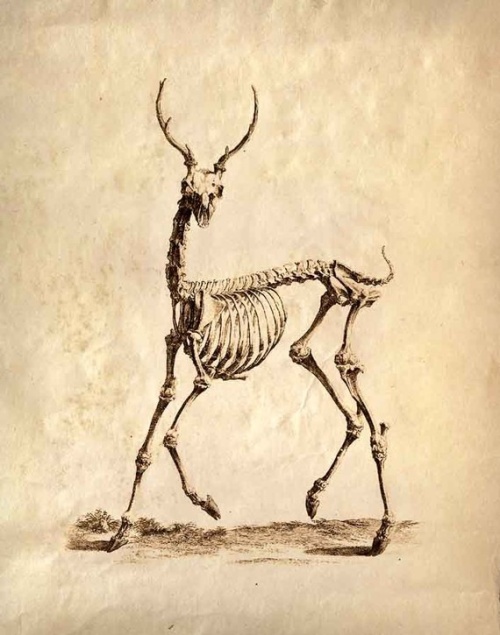

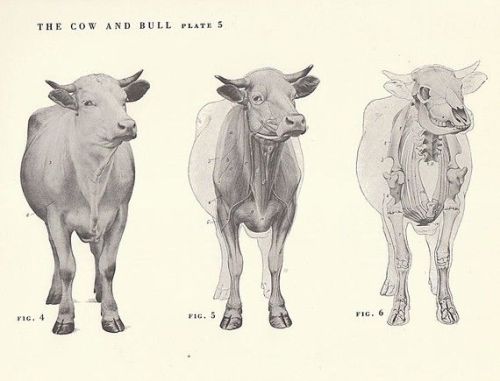

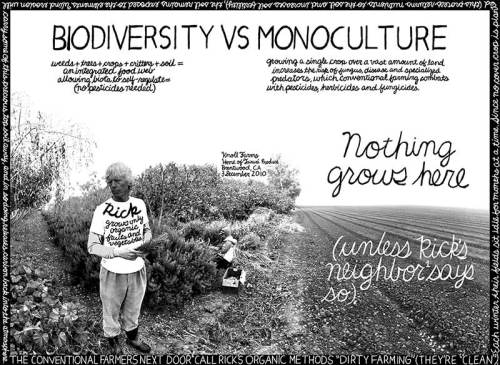

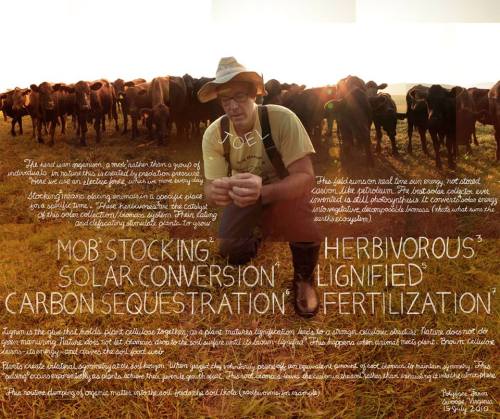

Shepherd: It dates back to the Neolithic Revolution, which was underway in most of Europe by 6,000 BC and gave us a new way of living: agriculture, permanent settlements, domesticated animals. We started taking charge of our environment. When you domesticate an animal, you become like a god to it. You determine with whom it will mate, and you own its babies. You choose what it will eat and when. And you determine the moment of its death. So at the start of the Neolithic Era humankind was radically altering its relationship with the world. The unforeseen consequence of that, which our culture hasn’t yet begun to appreciate, is that we also began to take control of the self in ways that created within us the same divisions we were creating in our relationship with the world. If you go back to the Indo-European roots of the English language, which date from the Neolithic, you find that the word for the hub of a wheel came from the word for navel. The hub is the center around which the wheel revolves. The metaphor suggests that the center of the self was located in the belly. The idea of being centered in the belly shows up in many cultures — Incan, Maya. There is a Chinese word for belly that means “mind palace.” Japanese culture rests on a foundation of hara, which means “belly” and represents the seat of understanding. The Japanese have a host of expressions that use hara where we use head. We say, “He’s hotheaded.” They say, “His belly rises easily.” We say, “He has a good head on his shoulders.” They say, “He has a well-developed belly.”

Buchbinder: This isn’t just a semantic issue, is it?

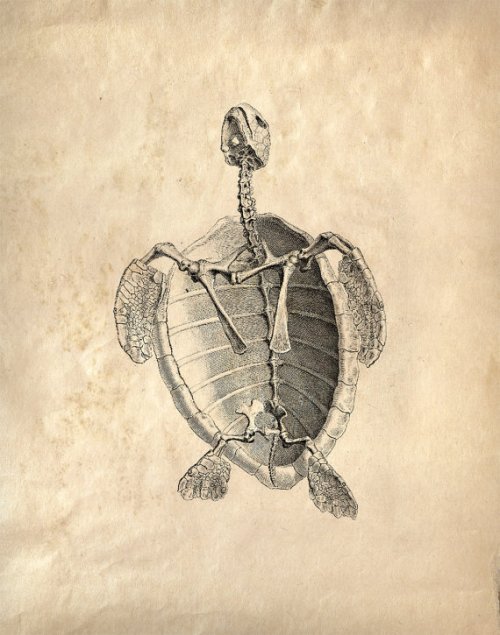

Shepherd: No, it’s deeper. These cultural differences point out that we have lost some choice in how we experience ourselves. Our culture doesn’t recognize that hub in the belly, and most of us don’t trust it enough to come to rest there. Our story insists that our thinking happens exclusively in the head. And so we are stuck in the cranium, unable to open the door to the body and join its thinking. The best we can do is put our ear to the imaginary wall separating us from it and “listen to the body,” a phrase that means well but actually keeps us in the head, gathering information from the outside. But the body is not outside. The body is you. We are missing the experience of our own being. To get a sense of what we have lost, it helps to appreciate the forces that carried us into the head. The Neolithic Revolution spawned two major changes in our story: the experiential center of the self, which had been located in the belly, began to migrate upward to the head; and the spiritual center of our culture began to migrate from the earth goddess up to the sky god. In mythological ways of thinking, the body and the world of nature generally are associated with the feminine, while the head and the realm of abstract ideas are associated with the masculine. By around 700 bc, we find the Greek poet Homer making frequent use of the word phren, which translates as both “mind” and “diaphragm.” So by Homer’s day the migration of our thinking was about halfway to the head, balanced between male and female. Some rich developments came out of that ancient Greek culture: the birth of Western science, philosophy, literature, theater. But by 350 bc or so the philosopher Plato locates the center of our thinking in the head. In his dialogue Timaeus the title character explains that the gods made us by fashioning the soul into a divine sphere, the cranium, and then gave it a vehicle, the body, to carry it around. So the head has the spark of divinity, and the body is a machine. That’s been our metaphor ever since. Our culture has been intolerant of attempts to reclaim this lost center of consciousness. In the early 1900s a Chicago anatomist named Byron Robinson wrote a book called The Abdominal and Pelvic Brain in which he describes the neurology of an independent brain in the gut. His work was quickly forgotten — it had no relevance to our cultural story. Then, in the late 1920s, Johannis Langley mapped out the autonomic nervous system. He said there were three divisions: the sympathetic, the parasympathetic, and the enteric. The enteric nervous system, which governs the gastrointestinal functions, is exactly what Robinson called the “abdominal brain.” Langley’s book became a classic, but the enteric nervous system was widely ignored, and students were taught that the autonomic nervous system has just two divisions. Finally, in the 1960s, Dr. Michael Gershon rediscovered the brain in the gut. In his book The Second Brain he describes how it took him fifteen years of presenting his research and answering refutations before his fellow neuroscientists capitulated and agreed that the neuromass in the belly is indeed an independent brain. [Gershon is a professor of pathology and cell biology at ColumbiaUniversity. — Ed.] Robinson, who first discovered the pelvic brain, was much freer in his assessment of its importance than scientists are today. He talked about it as the “center of life.” I completely agree with that. It is the center of one’s being.

Buchbinder: How does it meet the criteria for being a brain?

Shepherd: We shouldn’t imagine it as a lump of gray matter. The enteric brain is a web of neurons lining the gut. But it perceives, thinks, learns, decides, acts, and remembers all on its own. You can sever the vagus nerve, which is the main conduit between the two brains, and the brain in the gut just carries on doing its job. So they are both brains, but they are radically different. The enteric brain exists as a network that suffuses the viscera as a whole — which mirrors the way the female aspect of our consciousness feels the world around us as a whole, enabling us to exist in the present. The cranial brain, by contrast, is enclosed in the skull. And that mirrors the way the male aspect of our consciousness can separate itself from the world and create a subject-object relationship, enabling us to think abstractly. These two ways of engaging our intelligence reveal two different versions of the same world.

Buchbinder: Why bring “male” and “female” into it? Why associate “doing” with the male and “being” with the female?

Shepherd: The terms are imperfect, certainly, because people will tend to hear “men” and “women” — but I’m not talking about men and women. I’m talking about the complementary opposites that exist in each of us. Whether you are a man or a woman, there is both a masculine aspect to your consciousness and a feminine aspect. To come into wholeness is to realize the indivisible unity of these parts. At this point in our culture the male aspect has eclipsed the female aspect. I see this in both men and women. We have been taught to mistrust our bodies, to mistrust our intuition, to mistrust any information that is not analytical. This head-based, masculine perspective gives rise to three serious misunderstandings that drive our culture: we misunderstand what intelligence is, what information is, and what thinking is. Take our understanding of intelligence. We think it’s the ability to reason in an abstract fashion, something you can measure with an IQ test. So we remain blind to the impotence of reason in areas of vital concern to us. You cannot reason your way into being present. You cannot reason your way into love. You cannot reason your way into fulfillment. If you wish to be present, you need to submit to the present, and suddenly you find yourself at one with it. You submit to love. There’s that great quote from the Persian mystic Rumi: “Your task is not to seek love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.”

Buchbinder: If intelligence isn’t abstract reasoning, what is it?

Shepherd: It’s sensitivity — specifically a grounded sensitivity, because a reactive sensitivity isn’t able to integrate information. A sensitivity to music, to the flight of a swallow, to arithmetic relationship, to a child’s tears — all of these are forms of intelligence. And your sensitivity isn’t a static, permanent condition. Anything that increases it increases your ability to live more intelligently. Conversely, the constant noise and distractions of modern life have the opposite effect. The jackhammer you walk past on the street diminishes your intelligence by blunting your sensitivity.

Buchbinder: If this focus on the head began in the Neolithic, are you saying that we need to go back to the Mesolithic? What if the rise of consciousness to the cranial brain was an important part of our development as humans?

Shepherd: Our task at this point isn’t to go back. It’s not a matter of giving up the ability to think consciously or abstractly; it’s a matter of coordinating the two brains. Picture the first astronaut who went into orbit and took a photo of our planet. He brought that unprecedented perspective back home and showed it to people. Suddenly they were newly sensitized to what it means to be a citizen of the planet. They became slightly more intelligent about their relationship with it. I think that new sensitivity contributed to the range of environmental initiatives, such as the Earth Day movement and Friends of the Earth, that sprang forth in the years following that first photo of the earth from space. That story of the astronaut stands as a metaphor for the evolution of our consciousness, but we are only halfway through the journey. We have left our home in the belly and are now “in orbit” in the head, viewing the world from a new, somewhat remote vantage point. Just as the astronaut gains perspective by separating from the earth, we gain perspective by stepping back from the body, separating our consciousness from its sensations and dulling our awareness of them. The problem is, we don’t know how to bring those perspectives back home so they can be integrated. Without that integration our abstract perspectives can’t sensitize us to the world. They merely abet our ability to assert control over it. Our culture has a tacit assumption that if we can just gather enough information on ourselves and our world, it will add up to a whole. But when you stand back to look at something, there are always details that are hidden from you. The integration of multiple perspectives into a whole can happen only when, like the astronaut bringing the photo back to earth, we bring this information back to our pelvic bowl, back to the ground of our being, back to the integrating genius of the female consciousness. The pelvic bowl is the original beggar’s bowl: it receives the gifts of the world — of the male perspective — and it integrates them. As you bring ideas down to the belly and let them settle there, they sensitize you to who you are and eventually give birth to insight. Our task is to learn to trust that process. The central theme of my work is that our relationship with the body shapes our perceptions, which in turn direct the actions we take and guide the theories we generate. The atomic theory began as a philosophical concept that was first expounded by Democritus around the same time Plato declared the head to be the soul’s container and the body its vehicle. Having individuated ourselves from the world, we saw a reality made of individuated bits, a shattered universe of random pieces that have no real relationship with each other. And we still see it that way, because we live in the head. But that’s an alienating impoverishment of reality. Quantum mechanics has revealed that not even an electron exists as an individuated bit. It exists as part of a web of relationships. Our relationship with the body has similarly affected our politics, our corporate culture, our language, our cultural values — all of human history. Language tells us explicitly that the head should rule. You’d better have a good head on your shoulders. You need to get ahead. The bosses work in corporate headquarters and head up committees. Chief, captain, and capital all come from the Latin word for head, so Washington, DC, is literally the “head” of the U.S. We call the pope the “head” of the Roman Catholic Church. We could call him the “heart” of the Church, to emphasize that it’s an institution based on faith. Or we could call him the “lungs” of the Church, because spirit means “breath.” The Church might look to its original model, Jesus, who did not live from the head. Instead it’s organized as a top-down tyranny, with the pope as its “head.”