Some stories don’t require a translation. Some tales can satisfy your curiosity in the imagery itself. The story I am about to tell however, is one that asks that you be patient, and allow yourself to hang on every word:

As the story goes, the trip began with a motorcycle trip between North Africa and the North Cape. (Note: forgive the translation, all of these quotes were translated loosely from German, which is not my native tongue). Guenter Wamser explains that his horseback trek across the Americas was inspired by what he felt on his “Motorradodyssee”: “Disappointed about the impossibility of being able to capture a country in four weeks, grew in me the desire to someday take a journey of at least one year in duration. In 1986, I took leave of family and friends, from the regular salary of a secure existence. This was the beginning of a four-year Motorradodyssee in North and Central America.”

With that odyssey, Wamser discovered what it felt like to travel from a different perspective. He became fascinated by slow travel as he said, “It enabled me not only an eye for the spectacular scenery, but it opened me a different view of the magnificent details. I could now feel the country feel, grasp and comprehend.”

Guenter’s route through South America lasted five years, from 1994 to 1999. He trekked through Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador. A companion, Barbara Kohmanns joined Guenter on the journey from Ecuador to Mexico. Throughout the South American route, the team was Guenter and Barbara, the dog Liesl and the horses: Rebelde, Gaucho, Maxie, Samurai and Pumuckl.

The route through Central America took the team of Guenter, Barbara, dog Liesl and horses through Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico. This part of the journey stretched from 2001 to 2005.

Guenter wrote in his travel logs, “After 11 years and 20,000 km we finally reached Mexico. Each country smells different. But nowhere this impression was so strong as in Mexico. Mexico smelled like chili and fire, spirited life, like music. Mexico showed his picture book page: men with bright, wide-brimmed cowboy hats and trousers with oversized belt buckles. Mexico was the objective of the common journey of Barbara and me.”

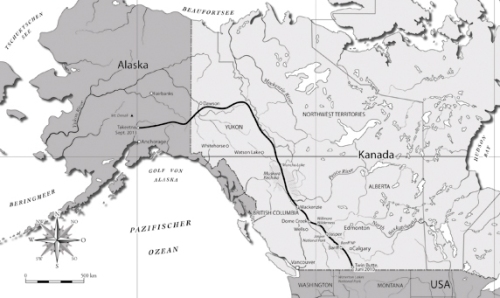

Crossing the border, the route across the United States was taken following the Continental Divide Trail, the CDC, which runs from the Mexican to the Canadian border. This trail is the dividing line of the tributaries of the Pacific Ocean in the west and the Atlantic Ocean in the east.

“In June 2007, the journey on the 5000 km long hiking trail along the Rocky Mountains began. In summer 2009, we reached the Canadian border. Why it took so long? Because intervening unique, beautiful landscapes are waiting to be discovered. The journey is the destination, the slowness is the beauty of traveling.

The CDT led us through the high plains of New Mexico, and the Land of Enchantment (Tierra de Encanto), passing the Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado, through the lonely plains of Wyoming to the natural wonders of Yellowstone National Park and up into the rugged mountains of Montana.

Our four Mustangs we adopted from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) . These wild horses were trained as part of a social project, the Colorado Wild Horse Inmate Program . In the course of this project the inmates get vocational training in the taming of horses and can be easily integrated back into society after their release.

Since 1971, wild mustangs in the United States are legally protected (Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971) and its stock is controlled by the BLM… Each year a portion of the wild horses captured by the BLM and given up for adoption.”

During this part of the trip, a new team member joined and another departed. Barbara Kohmanns discontinued and Sonja Endlweber embarked on the route with Guenter. The team that crossed the Rocky Mountain route was made up of Guenter, Sonja and animals: the dog Leni and four Mustangs Rusty, Dino, Lightfoot and Azabache.

This part of the trip lasted from June 2007 to September 2009.

The last leg of the transcontinental horseback ride for Guenter and Sonja was started in the Spring of 2013 from the United States- Canada border to Alaska. Even after their epic trip on horseback is finished, Sonja, Guenter and Barbara continue to travel around Europe giving lectures and doing showings on their amazing adventure.

Getting a glimpse at their journey and the route they followed in crossing over continents with their horses, I feel a deep stirring in my soul. Something in me is waking up, stretching, and saying more loudly each day, your dreams are possible. You may be told you’re crazy, and that your dreams are unrealistic, but if crossing two continents on horseback in the span of twenty years is a reality for those who dared follow their dreams and do the work necessary to make it happen, then why on earth do we dare not live ours?

Click here to read more of the story of the transcontinental ride from South Patagonia to Alaska